A form of immunotherapy known as “chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy” alters the immune system of a cancer patient to make it more adept at locating and eliminating cancer cells. The immune system of a human is extremely intricate and encompasses numerous distinct cell types and bodily systems. A lymphocyte is one of these cells; it is a type of white blood cell that fights infection. There are numerous varieties of lymphocytes, and one of them is known as a T-cell. T cells are used in CAR T-cell therapy because they often eliminate malignant cells and virus-infected cells.

Cancer cells are known to evade the immune system’s regular defenses, but thanks to CAR T-cell treatment, some cancer cells can now be more easily found and eliminated by T cells.

What is CAR T-Cell Therapy?

T-cells are effective at warding off infections. However, it can be challenging for them to distinguish between a cancer cell and a normal cell. In order to avoid detection, the cancer cells might conceal themselves.

Researchers are looking for strategies to train T-cells to recognize cancer cells. CAR T-cell therapy is one method that could be used to achieve this.

How does CAR T-Cell Therapy Work?

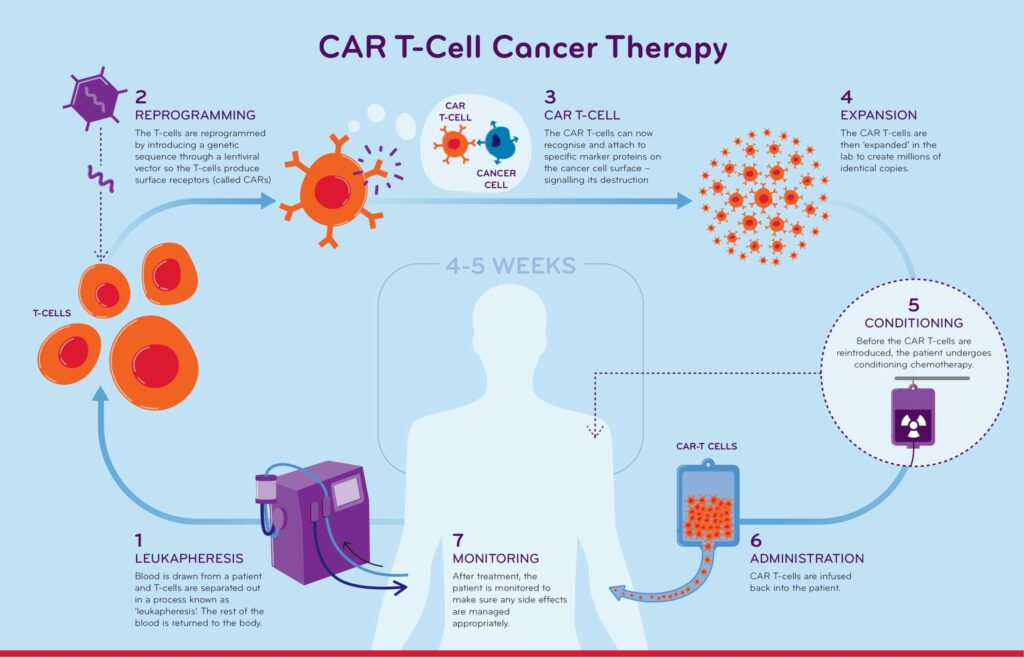

For this kind of therapy, a cancer patient must first be sent to a specialized facility. Then, a collection of their T-cells is required. It is important to understand that prior cancer treatments frequently have an impact on T-cells and may leave them less healthy. When T-cells are transformed into CAR T- cells, they should ideally be in the best condition. This frequently implies that a person’s T-cells must be collected during a break in therapy. This means that in order to collect as many healthy T-cells as possible, the doctor needs take special care to ensure that cancer won’t be overly active or result in too many symptoms while therapy is delayed.

The T-cells are gathered via a procedure known as “Apheresis”, once a predetermined length of time has passed without treatment. During apheresis, the patient’s blood is cycled through a device that removes T-cells before returning the remaining blood to them. After that, a manufacturer receives the cells and turns them into CAR T-cells, which normally takes 3 to 6 weeks. The person’s regular T-cells are activated, proliferated, and infected with a virus during the manufacturing process, which leads to genetic change and the addition of the CAR to the T cell. The CAR T-cells are then transported back to the cancer patient’s doctor frozen.

Before injecting the CAR T-cells into the cancer patient, the doctor administers a brief course of chemotherapy termed lymphodepletion over the course of two to three days. This prevents the body’s immune system from misinterpreting the CAR T-cells as aberrant and rejecting them. The CAR T-cells are then removed from the freezer, defrosted, and administered through the blood in a manner akin to a blood transfusion.

At this point, the CAR T-cells begin to function. They move about the body looking for cancer cells, activating, growing, utilizing cytokines to recruit support, and then eradicating cancer.